Under the right conditions, electrons can “freeze” into an unusual and highly ordered solid state. In a groundbreaking achievement, physicists at Berkeley Lab have successfully captured the first-ever direct images of this phenomenon, revealing a new quantum phase of matter known as the Wigner molecular crystal.

At its core, the Wigner molecular crystal is a unique variation of a solid electron phase. Unlike typical Wigner crystals, where individual electrons arrange themselves into a regular lattice, the Wigner molecular crystal features groups of electrons that settle together in each lattice position, forming what can be described as “electron molecules.”

Electrons are typically free to move through materials in a somewhat disordered fashion, acting like a liquid. However, under the right conditions, such as when their motion is slowed down significantly, the electrostatic repulsion between the electrons takes over. Since electrons carry the same negative charge, they naturally repel each other. As their movement slows, they push apart and lock into stable positions at a specific distance from one another. This creates the Wigner crystal phase.

To create the Wigner molecular crystals, the researchers developed a novel framework to help guide the electrons into “molecules.” The process begins with a thin, 49-nanometer layer of hexagonal boron nitride, which is then stacked with two layers of tungsten disulfide, each only a single atom thick. One layer is rotated by 58 degrees relative to the other, forming a moiré superlattice structure.

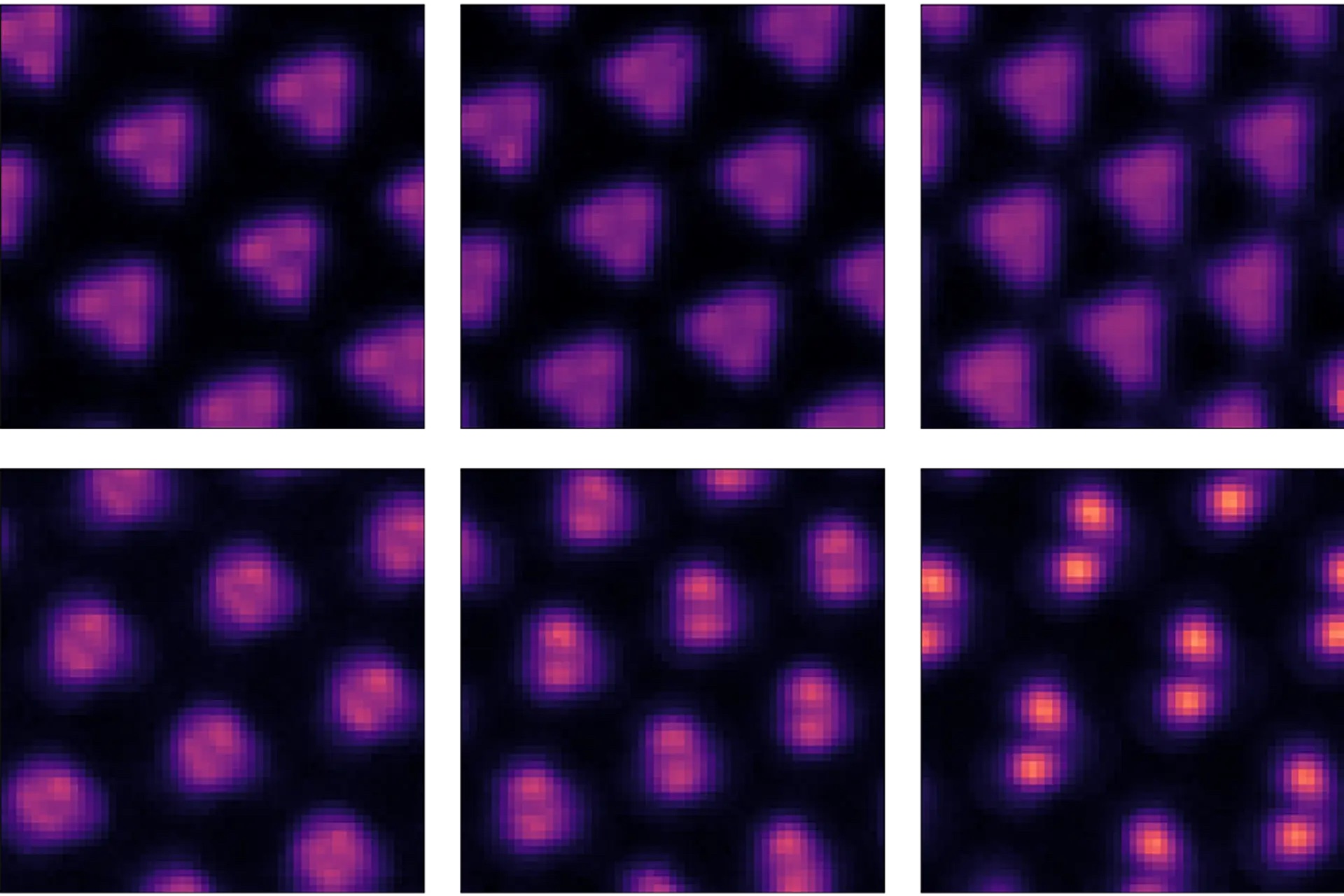

Next, the team doped the material with electrons, which caused them to group into units of two or three electrons within each lattice cell. These small clusters of electrons formed the Wigner molecular crystal, a structure previously theorized but never directly observed.

The next challenge was to image this delicate new structure. Scanning tunneling microscopes (STM), commonly used to study materials at the atomic scale, were deemed unsuitable because the electric field produced by the microscope’s tip could disturb the fragile electron arrangement. However, the researchers found a way to minimize this interference, enabling them to capture the first clear images of the Wigner molecular crystal.

This breakthrough provides new insights into the behavior of electrons at extreme conditions, opening the door for further exploration of exotic quantum phases that could have applications in areas such as quantum computing and materials science.

By Impact Lab