In medicine, some moments arrive that feel like science fiction made real. One of those moments just happened: scientists in China have transplanted a genetically engineered pig lung into a human body—and kept it alive for nine days. Reported in Nature Medicine, this milestone marks the first time a lung from another species has functioned inside a person, and while challenges remain, it signals a future where the global shortage of donor organs may no longer be a death sentence.

Every day, roughly 13 people die waiting for an organ transplant. Nearly 90,000 people in the United States alone are waiting for kidneys, while thousands more wait for hearts, livers, and lungs. The bottleneck is supply: there simply aren’t enough donors. Xenotransplantation—using organs from animals—has long been considered a potential solution, but the immune system is ruthless. It treats pig organs as foreign invaders, triggering catastrophic rejection.

The latest breakthrough represents decades of careful genetic tailoring. Scientists used CRISPR to strip away pig genes responsible for immune-triggering proteins and added human immune-regulating genes to disguise the organs as “friend, not foe.” The donor came from a specially bred Bama Xiang minipig, genetically engineered to produce organs closer to human compatibility.

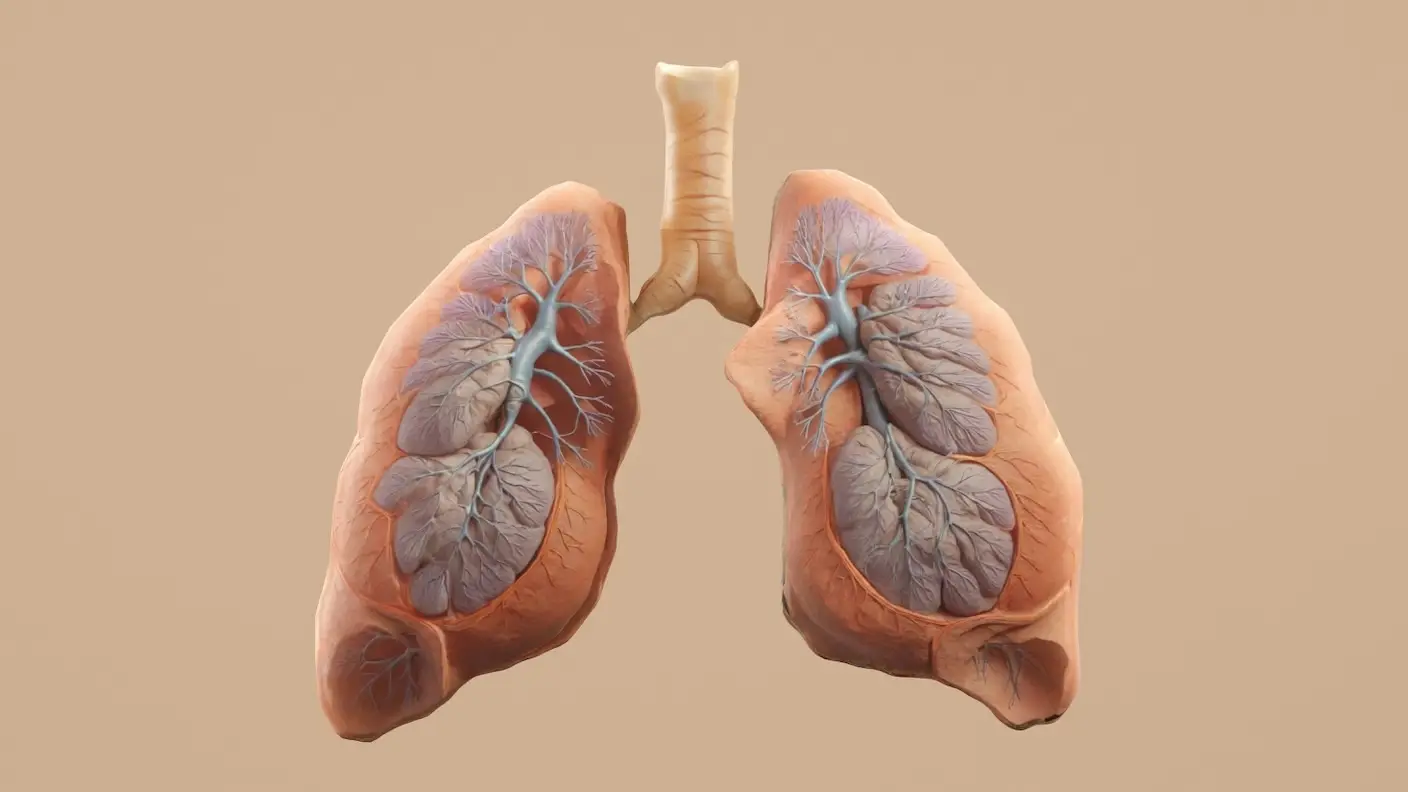

The lung was transplanted into a 39-year-old brain-dead man whose family consented to the experimental procedure. Within a day, the lung stabilized and began functioning as expected, supplying oxygen to the bloodstream. By medical standards, that was remarkable—lungs are notoriously delicate, vulnerable to damage during transplantation, and exposed to pathogens through every breath. For over a week, the organ not only worked but showed signs of healing and integrating with the body.

But the immune system did not remain silent. By the second day, inflammatory cells swarmed the transplanted lung. Antibody levels spiked on days three and six, creating a cascade of rejection activity. Despite this, the lung persisted, partially recovering by day nine. The researchers ultimately ended the experiment at the family’s request, but the trial proved something extraordinary: pig lungs can function in humans, at least for a time.

Why does this matter? Because lungs are among the hardest organs to transplant successfully. Unlike hearts or kidneys, they face not only blood-based rejection but also constant exposure to airborne threats. If scientists can solve the lung challenge, then the pathway to routine xenotransplantation of other organs becomes far clearer.

Future refinements will focus on immune control. More sophisticated gene edits, combined with next-generation immune-modulating drugs, could allow pig lungs to last weeks, months, or even years. Eventually, we could see complete organ replacement for patients with end-stage lung disease, offering hope to those who today face dwindling options and long waitlists.

This breakthrough also hints at a broader shift in medicine: designing living spare parts. Instead of relying on the tragic unpredictability of human donation, hospitals could one day order customized organs on demand, grown in pigs whose genetics have been fine-tuned for compatibility. No more waiting lists. No more shortages. The transplant system, once defined by scarcity, could evolve into one defined by abundance.

For the family of the first recipient, the trial was a gift to future generations—a courageous step into the unknown. For the rest of us, it is a glimpse of a coming era where breathing with a pig’s lung is not an experiment, but a standard treatment. The frontier of medicine has always been about crossing lines we once thought uncrossable. With each successful xenotransplant, we are learning that those lines are closer to vanishing.

Read more on related breakthroughs: