By Futurist Thomas Frey

When Trash Becomes the Most Valuable Resource on Earth

My recent column on robotic earthworms mining landfills has generated intense response, with many questioning whether the concept is actually feasible. The skepticism is understandable—we’re talking about autonomously burrowing through compacted garbage, identifying and separating dozens of material types, and extracting valuable resources from what we’ve treated as worthless waste for generations.

But here’s what the skeptics are missing: the physics works, the economics are compelling, and the environmental imperative is absolute. We’ve buried trillions of dollars of valuable materials in landfills worldwide. The person who figures out how to automatically recycle the world’s trash won’t just build a profitable business—they’ll win a Nobel Prize and fundamentally reshape how civilization manages resources.

Let me walk you through exactly how this could work, what still needs to be invented, and why this might be the most important engineering challenge of the next decade.

The Scale Nobody’s Imagining: These Aren’t Small Machines

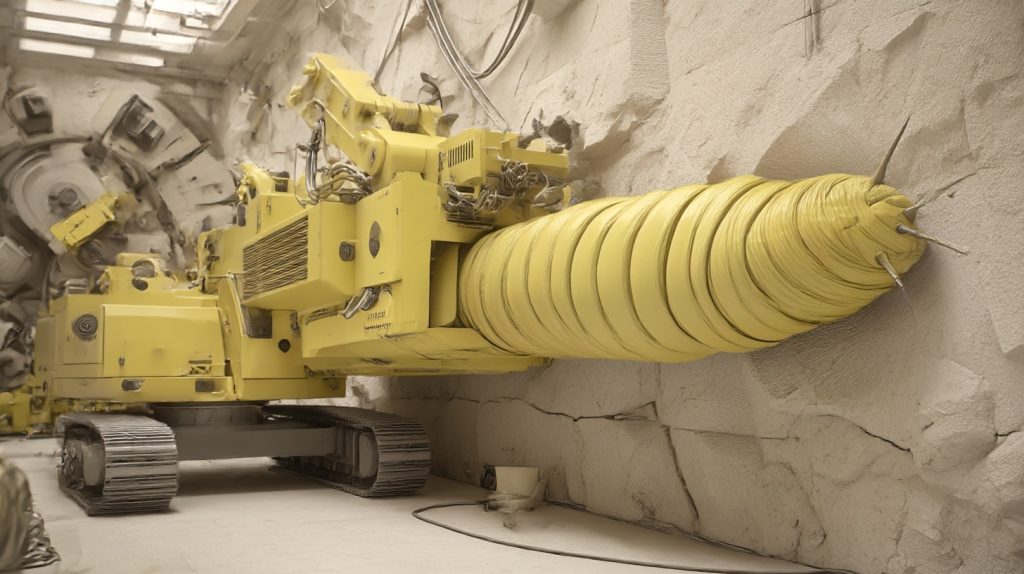

When people hear “robotic earthworm,” they’re probably imagining something the size of an actual earthworm, or perhaps a large snake. That’s orders of magnitude too small. We’re talking about machines the size of subway tunnel boring equipment—10 to 15 meters in diameter, 50 to 100 meters long. These are massive industrial platforms that happen to move through landfills rather than rock.

Think of them more like mobile processing plants that burrow. The scale is necessary because the separation processes require space, and processing volume requires size. You can’t efficiently separate tons of material per hour through a system the size of a car. You need industrial-scale equipment, which means industrial-scale platforms.

The largest tunnel boring machines currently operating are over 17 meters in diameter. A landfill mining earthworm would be comparable in scale but optimized for softer, more heterogeneous material. The advantage over rock tunneling is that compacted garbage requires less cutting force, allowing more of the machine’s volume to be dedicated to processing equipment rather than excavation power.

The Robotic Earthworm: More Than Just a Burrowing Machine

The front end excavates material using rotating cutting heads similar to tunnel boring machines but scaled for heterogeneous waste rather than rock. As it burrows, it ingests everything—plastics, metals, organics, glass, textiles, electronics, mixed materials. The excavated material gets conveyed backward through the earthworm’s body, where the separation processes happen.

The first stage inside the earthworm is mechanical processing. Industrial shredders and grinders reduce everything to manageable particle sizes, probably 2-5 centimeters depending on material type. This isn’t revolutionary technology—we have industrial shredders that can process entire cars. The innovation is hardening these systems to operate continuously in hostile environments.

After shredding, the material enters a cascade of separation processes happening sequentially inside the earthworm’s body. This is where the real engineering challenges concentrate, but also where existing technologies provide clear pathways forward.

Power and Output: Rethinking the Infrastructure

Rather than trailing power cables that would tangle and limit movement, the earthworm likely uses a hybrid approach. Onboard battery systems provide power for short-term operations and mobility. When the earthworm reaches optimal processing locations, it connects to modular power stations that get positioned throughout the landfill as mining progresses. These power stations could be solar arrays on the landfill surface, generators, or grid connections, depending on the location.

For material output, instead of continuously trailing collection containers, the earthworm periodically reverses direction, backing out through the tunnel it’s created to deposit separated materials at collection points. The tunnel itself, reinforced by the compacted waste around it and possibly stabilized with quick-setting foam or mesh, becomes a reusable pathway. The earthworm can advance, fill its collection chambers, reverse to empty, then advance again along the same or adjacent tunnels.

Alternatively, multiple smaller transport robots shuttle between the earthworm and surface collection points, carrying separated materials through the tunnel network. This is similar to how mining operations use autonomous haul trucks, just scaled down and adapted for tunnel environments.

The Separation Cascade: How You Extract Value from Chaos

Stage One: Density Separation

The first major separation uses gravity and density differences. Air classification blows lighter materials (plastics, paper, organics) upward while heavier materials (metals, glass, ceramics) fall downward. This is proven technology used in recycling facilities today—we’re just implementing it inside a mobile platform.

Jig separation follows, using pulsating water flows to stratify materials by density. Steel sinks fastest, then aluminum, then various plastics. This creates distinct layers that can be mechanically separated. Mining operations have used jig separation for over a century. The challenge is making it work continuously at scale inside a mobile system processing unpredictable mixed waste.

Stage Two: Magnetic and Eddy Current Separation

Ferrous metals get extracted via powerful electromagnets—straightforward proven technology. Non-ferrous metals like aluminum and copper get separated using eddy current separators that induce currents in conductive materials, creating magnetic fields that repel them from the waste stream. This technology is mature and reliable in stationary recycling facilities. The adaptation challenge is power consumption and continuous operation in mobile platforms.

Stage Three: Spectroscopic Identification

Here’s where we need significant innovation. Near-infrared spectroscopy can identify different plastic types, but current systems require relatively clean, individual items. We need spectroscopic systems that can identify materials in dirty, mixed streams at high speed. The technology exists in laboratories—we’re talking about engineering it for industrial robustness and speed.

X-ray fluorescence can identify specific metals and alloys even when mixed and dirty. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy can identify nearly any material by analyzing the plasma created when you vaporize a tiny sample. Both technologies exist. What we need is miniaturization, speed increases, and integration into continuous processing systems.

Stage Four: Automated Sorting

Once materials are identified, robotic sorting systems direct them into appropriate collection streams. Industrial robotic arms can already pick items at impressive speeds. What we need is reliability in dirty environments and the ability to handle the volume—probably multiple parallel sorting systems operating simultaneously.

The separated materials get stored in different collection chambers within the earthworm’s body. Steel in one compartment, aluminum in another, different plastics in separate chambers, glass, copper, rare earth elements from electronics—each into optimized storage until the earthworm returns to surface collection points to empty its payload.

What Still Needs to Be Invented

The individual technologies largely exist. What we need to invent is the integration, optimization, and autonomous operation. Specifically:

Adaptive Power Management: Systems that balance mobility, processing, and separation operations while optimizing energy use based on material density, composition, and value concentration in different areas of the landfill.

Autonomous Navigation: The earthworm needs to map the landfill in three dimensions, identify areas of high-value concentration, and navigate optimally without human guidance. This is sophisticated but achievable—autonomous vehicles already navigate complex environments. Landfills are actually easier than traffic because they’re static.

Spectroscopic Speed and Accuracy: We need material identification systems that work at industrial speeds on dirty, mixed materials. This requires innovation in sensor technology, machine learning for material identification, and novel optical systems that can see through contamination.

System Integration: Making all these processes work together continuously, reliably, in hostile environments represents a massive engineering challenge. But it’s an engineering challenge, not a physics impossibility.

Tunnel Stability: Ensuring the tunnels remain stable and navigable for repeated use, possibly through automated reinforcement systems that spray stabilizing compounds or install support structures as the earthworm advances.

Self-Maintenance: The earthworm needs to operate for extended periods with minimal human intervention. This means self-diagnostic systems, redundant critical components, and possibly self-repair capabilities for common failure modes.

The Economics That Make This Inevitable

Here’s why someone will solve this: the economic value is staggering. Landfills contain approximately 50-100 billion tons of material globally. Even conservative estimates suggest trillions of dollars in recoverable value—metals, plastics that can be reprocessed, rare earth elements from discarded electronics.

A single landfill contains more accessible rare earth elements than most mines. The concentration of valuable materials in e-waste sections of landfills exceeds natural ore deposits. We’ve essentially created artificial mines of presorted materials, we just need the technology to extract them efficiently.

The environmental value is equally compelling. Every ton of material recovered from landfills is a ton we don’t need to mine, reducing environmental destruction, energy consumption, and carbon emissions. Cleaning up landfills recovers land for productive use. Removing toxic materials prevents groundwater contamination.

Why This Wins a Nobel Prize

The person who solves automated landfill mining won’t just create a profitable business—they’ll fundamentally change how civilization manages resources. We’ll be able to clean up every country in the world, recovering trillions in materials while reclaiming land and preventing environmental damage.

Developing nations with limited natural resources but abundant landfills suddenly have mines worth more than traditional extraction. Environmental cleanup becomes profitable rather than costly. The circular economy becomes economically inevitable rather than aspirational.

This is Nobel Prize-level impact because it solves multiple existential challenges simultaneously: resource scarcity, waste management, environmental remediation, and provides economic development pathways for nations currently dependent on raw material extraction.

Final Thoughts

The robotic earthworm concept isn’t science fiction—it’s engineering extrapolation from existing technologies combined in novel ways. The skeptics asking “is this feasible?” are asking the right question. The answer is yes, with significant engineering innovation required but no physics violations blocking the path.

Someone will figure this out in the next decade because the economics are too compelling and the environmental necessity too urgent. When they do, they’ll have built not just a company but a solution to one of civilization’s most pressing challenges. And yes, they’ll deserve that Nobel Prize.

After all, the person who transforms the world’s garbage from liability into asset, who makes environmental cleanup profitable, who gives developing nations access to material wealth they’ve been sitting on for decades without realizing it—that person will have earned recognition as transformative as any scientific breakthrough.

Related Articles:

Mining Our Garbage: How Robotic Earthworms Will Turn Landfills Into Gold Mines

Building a More Valuable Human: Why Your Life Is Worth $2 Billion (And Rising)

The Most Profitable Question in Business: What’s Still Missing in 2025?