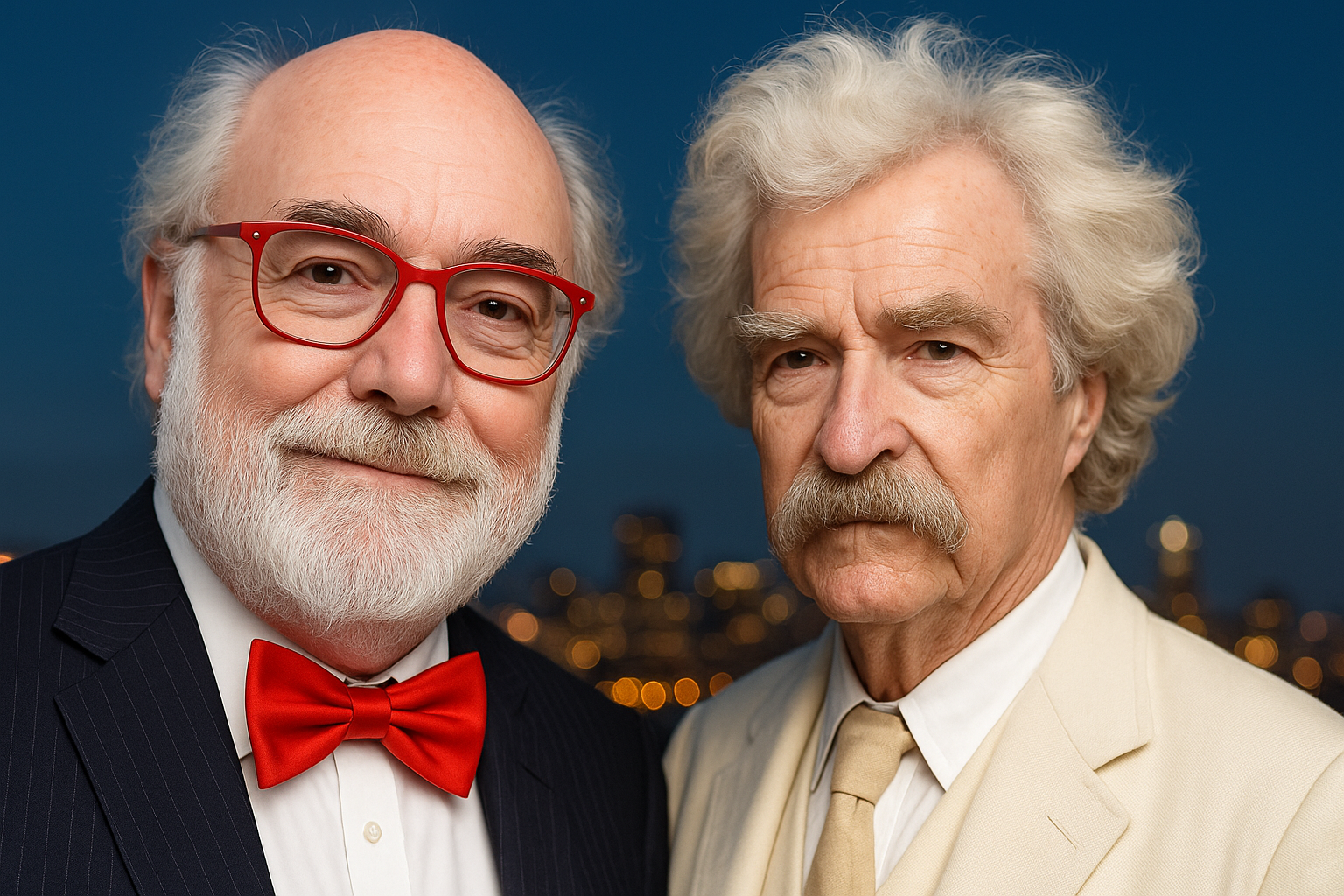

By Futurist Thomas Frey

When the Past Meets the Future Over Whiskey

I found myself in a peculiar dream last night—sitting across from Mark Twain in what appeared to be a riverboat saloon, though the Mississippi outside the windows looked suspiciously like data streams. He was smoking a cigar, naturally, and eyeing me with that mixture of amusement and skepticism he reserved for people trying to sell him something.

“So, Mr. Frey,” he began, “you’re here to tell me about the wonders of your automated age. Driverless carriages, flying machines that deliver packages, and thinking engines that’ll make human brains obsolete. Am I getting the gist of your pitch?”

“It’s more nuanced than that,” I said. “We’re building AI systems that can—”

“Let me stop you right there.” He took a long draw from his cigar. “Every age thinks it’s inventing something new. In my time, they said the steamboat would transform civilization. And it did—transformed it into a system where a few men owned the boats and everyone else worked for them. Tell me how your robots are different.”

On Jobs and Purpose

“Well,” I said, “AI and robots will handle dangerous, repetitive work. Free humans to pursue creativity, meaning, purpose.”

Twain laughed—that deep, cynical laugh that made you question everything. “Free them to pursue purpose? Son, I’ve watched humanity pursue purpose for sixty years. You know what most people do when freed from work? They find new work, because purpose isn’t something you pursue in leisure. It’s something you get from being needed.”

“But surely—”

“No ‘surelys’ about it. You’re telling me that machines will do all the work while humans contemplate philosophy and paint watercolors? I’ve known working men. They don’t want to paint. They want to be useful. You’re not freeing them—you’re making them unnecessary. And a man who’s unnecessary is just a burden who’s still breathing.”

He had a point, though I wasn’t ready to concede it. “We’re developing systems to help people transition. Retraining programs, universal basic income—”

“You’re going to pay them to be useless?” Twain shook his head. “That’s not kindness. That’s creating a permanent class of dependents and calling it progress. But please, continue. Tell me about these thinking machines.”

On Artificial Intelligence

“AI can process information faster than any human,” I explained. “Make connections we’d never see. Generate insights that—”

“Generate insights?” Twain interrupted. “Or generate approximations of insights that sound plausible because they’re grammatically correct? I’ve read plenty of grammatically correct nonsense in my day. Hell, I’ve written some of it. The question isn’t whether your machine can string words together. It’s whether it has anything worth saying.”

“But AI is learning to be creative. Write stories, compose music—”

“Learning to imitate creativity,” he corrected. “There’s a difference between doing what creative people do and being creative. A parrot can repeat Shakespeare. Doesn’t make it a playwright.”

I shifted tactics. “What about AI companions? People who are lonely, isolated—AI can provide connection, conversation, emotional support.”

Twain’s expression darkened. “You’ve invented an imaginary friend for adults and you’re charging them for it. That’s not solving loneliness—that’s monetizing it. A lonely man talking to a machine that’s programmed to agree with him isn’t making a connection. He’s talking to himself and paying for the echo.”

On Driverless Cars

“What about safety?” I pressed. “Driverless cars will save thousands of lives by eliminating human error.”

“Human error,” Twain mused. “Yes, I suppose removing humans from driving would reduce human error, much like removing water from swimming would reduce drowning. But you’ve missed the point. The error isn’t in the driving—it’s in the hurrying, the drinking, the stupidity. Your machine won’t fix stupid. It’ll just create new ways for stupid to manifest.”

“But the efficiency gains—”

“Efficiency.” He said the word like it tasted bad. “We’re always pursuing efficiency. Efficient factories created industrial slums. Efficient farming created dust bowls. Efficient communication gave us spam telegrams—or whatever you call them now. Email? Every time humans pursue efficiency, we discover new inefficiencies we couldn’t have imagined. What fresh hell will your efficient transportation create?”

On Drones and Surveillance

“Speaking of transportation,” I said, trying to regain control, “delivery drones will revolutionize logistics. Packages delivered in minutes instead of days.”

“Marvelous,” Twain said dryly. “We’ll get our unnecessary purchases delivered by flying mechanical insects that watch everything we do. In my day, if someone wanted to spy on you, they had to at least pretend they weren’t. You’ve eliminated the pretense entirely and called it convenience.”

“They’re not spying—they’re delivering.”

“Son, any device that can see where you are can be used to watch what you’re doing. You think the people who own these flying contraptions won’t notice that? They’ll deliver your packages and catalog your habits, and you’ll thank them for the privilege.”

On What We’re Really Building

I set down my drink. “So you think it’s all foolish? All of it?”

Twain was quiet for a moment, considering. “I think you’re building exactly what every generation builds—solutions to problems that create bigger problems you can’t see yet. The steamboat solved transportation but created monopolies. The railroad connected the nation but destroyed communities. Your robots and thinking machines will solve something, I’m sure. But they’ll create dependencies and disruptions you’re not accounting for.”

“Such as?”

“Such as what happens when nobody needs anyone anymore. When machines do the work, provide the companionship, make the decisions. You’re not building tools—you’re building replacements. And when humans are replaced, what exactly are they for?”

“For living. For experiencing. For being human.”

“And what,” Twain asked quietly, “does that mean when being human doesn’t mean being necessary to anyone or anything?”

Final Thoughts

I woke up then, unsettled. Twain’s questions lingered: Are we building liberation or creating dependence? Solving loneliness or monetizing it? Freeing humans from drudgery or rendering them unnecessary?

The man had a gift for cutting through optimism to uncomfortable truths. Maybe that’s what we need more of—not cheerleaders for innovation, but skeptics who ask what we’re actually trading away for these shiny new capabilities.

After all, as Twain might say: “The future is a wonderful place—I just hope we survive getting there.”

Related Articles:

The Emptiness of Being Unnecessary: When Nobody Needs You Anymore

The Loneliness Paradox: When AI Makes You Feel Connected While You Slowly Disappear

When Machines Start Talking to Each Other: The Bizarre Choreography of Autonomous Everything