Sometimes the most radical ideas hide in plain sight. Imagine an aircraft smaller than a dime, featherlight, with no propellers, no solar panels, and no engines—yet capable of rising into the sky powered entirely by the heat of the sun. No fuel tanks. No batteries. Just geometry, light, and physics conspiring to lift human curiosity higher than ever before. These tiny flyers are the beginning of an entirely new class of vehicles: machines that sip energy from the environment itself and drift into unexplored frontiers.

For decades, the mesosphere—the layer of atmosphere between 50 and 80 kilometers above the Earth’s surface—has remained an almost unreachable frontier. It is too high for balloons and aircraft, yet too low for satellites. Scientists call it the “ignorosphere” because of how little we know about it. But this neglected frontier is not empty. It holds clues about high-altitude clouds, meteoric dust, and electrical storms that shape our weather systems and atmospheric balance. Until now, we’ve lacked the tools to study it up close. These new sun-heat-powered flyers may change that within a decade.

The design traces its lineage to a Victorian curiosity: a spinning pinwheel with black-and-white vanes inside a glass bulb, a toy that baffled great minds like Maxwell and Einstein. It turns out the toy’s movement is powered not by radiation pressure, but by gas molecules colliding unevenly with surfaces heated at different rates. This effect, called photophoresis, becomes especially powerful at low pressures, such as in the mesosphere or on Mars. Modern researchers have turned this 19th-century amusement into a 21st-century platform for exploration. Their devices are wafer-thin, made of perforated aluminum oxide layers thinner than a human hair, with a chromium-coated underside that heats more than the top layer. Sunlight creates a steady stream of air movement, generating lift without a single moving part. In essence, they are micro-rockets without engines, tapping into thermal gradients as their propulsion system.

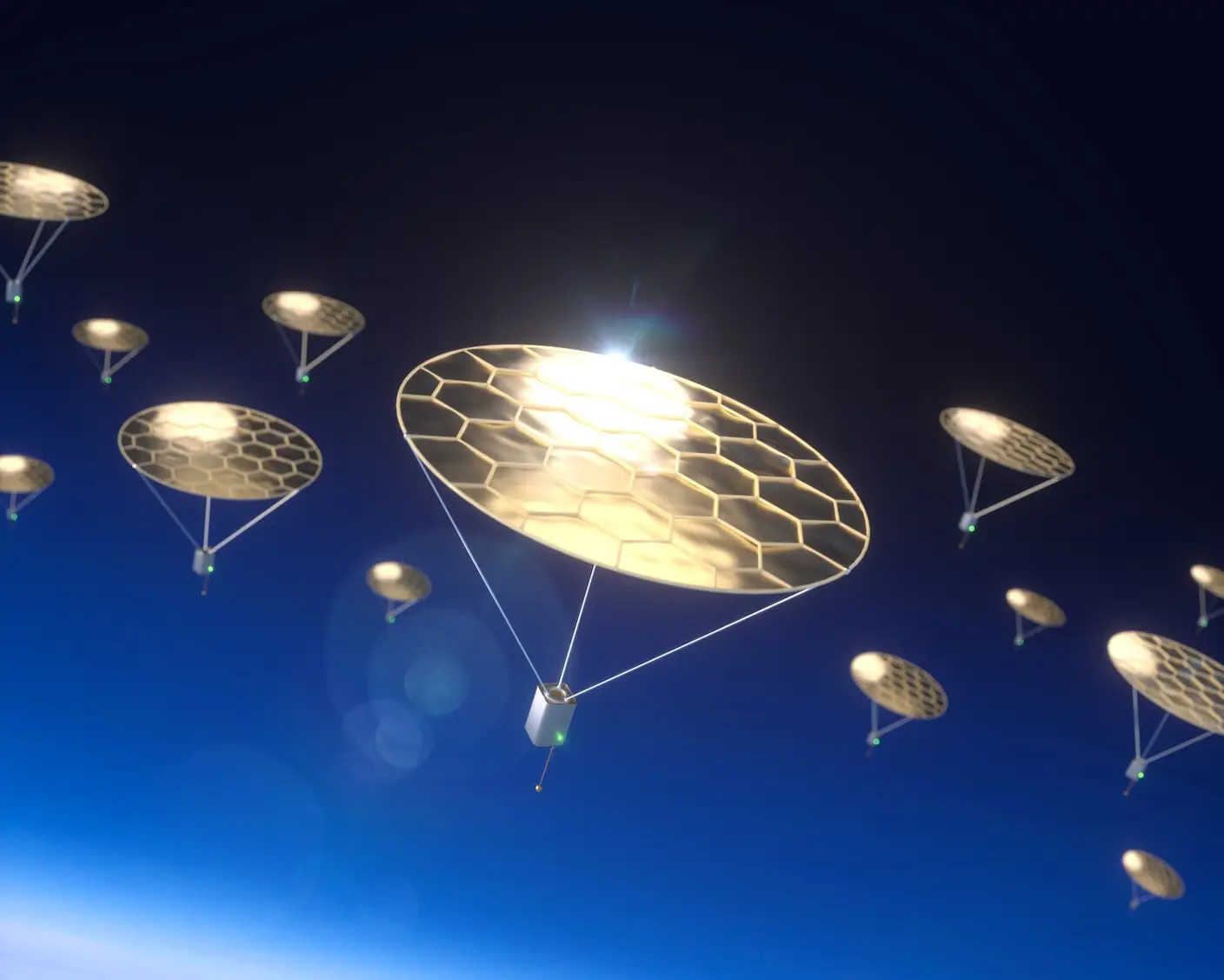

Computer simulations show that palm-sized versions of these flyers could carry small payloads—a radio antenna, a chemical sensor, even tiny microelectronics—high into the mesosphere. They could remain aloft for weeks, powered not only by sunlight but also by Earth’s own infrared emissions at night. That means fleets of them could hover indefinitely, mapping elusive atmospheric processes in real time. On Earth, such swarms could revolutionize how we monitor weather, detect rare lightning phenomena, and track cosmic dust. On Mars, they could do even more. Mars’ thin atmosphere is ideal for photophoretic flyers, and their lightness makes them easy to ship aboard rockets. Equipped with miniaturized instruments, they could ride Martian winds for months, sending back data on dust storms, water vapor, and surface weather in ways no rover or orbiter ever could.

The power of this technology lies not in brute force but in elegance. Conventional aircraft and spacecraft rely on heavy batteries, fuel tanks, or bulky solar panels. These flyers need none of that. They’re a glimpse into a future where machines harness ambient energy flows—the heat of the sun, the movement of gases, the very physics of light and air—to perform tasks that once required enormous infrastructure. It’s not just a breakthrough in aerospace; it’s a shift in how we think about energy and motion itself.

What makes this discovery truly provocative is the scalability. If swarms of these devices can be deployed cheaply, we may soon cover the atmosphere with a new sensory layer, an invisible network of autonomous probes mapping conditions with unprecedented precision. In planetary exploration, they could be the key to turning distant worlds into living laboratories. Instead of sending billion-dollar rovers crawling across a few square miles, we could release thousands of sun-powered scouts, turning the skies of Mars, Venus, or Titan into flowing rivers of data.

We’ve long dreamed of aircraft that fly forever, powered only by sunlight. The Wright brothers conquered the skies with wood and cloth. Today, scientists are doing the same with materials thinner than a strand of hair, no engines required. These tiny craft are not toys—they are the seeds of a new era where flight is no longer constrained by engines, fuels, or even our atmosphere. The future of exploration may be as small as a dime, but its implications stretch all the way to the stars.

Read more on related breakthroughs:

- Self-powered flyers could transform planetary exploration

- Sunlight-driven microfliers open new frontiers in aerospace